March of the Living

An emotional account from AJR Volunteer Coordinator, Naomi Kaye, of her recent experience on the March of the Living.

On Monday 9 April I headed off on an early flight from Luton airport with group G to join the rest of the March of the Living UK contingent. 270 of us, on a pilgrimage through towns, camps and ghettos scarred by the Holocaust in the south and east of Poland. The aim of March of Living International is to build up a full picture of Jewish people throughout Poland’s history and the UK made up the some of the 11,000 who were joining in from all corners of the world.

There were seven buses in total, each with its own team of people escorting us through our jam-packed itinerary. On my bus Michael Wegier, Chief Executive of the UJIA, was our bus leader, ensuring we were in the right place, at the right time. Clive Lawton, our educator, who engaged us effortlessly with the facts throughout our four-day trip. Bartek was our polish educator, offering a helping hand to fill in the blanks and give a Polish perspective on what we saw. Tomek, our security guard was always close by, but despite my preconceptions of Poland, I never felt unsafe. We also had our own survivor, Ivor Perl, who travelled with us throughout our journey, but with whom, despite his trepidation and anxiety of being back in the place that inflicted so much pain, he saw the need to share his experiences with the next generation.

After landing in Lublin, Poland we took a short journey on our coach to the medieval castle near the Old Town district. After a quick packed lunch, sitting on the wall of one of the oldest royal residences, dating back to 1336 we were introduced to the history of this city. It was here that King Casmir III granted the Jews permission to settle on the outskirts of the city. Later on, King Sigismund I permitted Jews to settle near the castle. Hearing how the Jews had full autonomy, their own land to build on and shops to sell their goods, helped to build up a picture in my head of Jewish people being respected and supported.

Hearing and seeing the evidence that Poland was once known as Paradisus Ludaeorum, Paradise for the Jews, home to the largest and most significant Jewish community in the world was absolutely fascinating. This was our first pit stop and I was starting to feel happy thoughts, intrigued and impressed that Jews were held in high regard throughout Poland. I relished hearing about Jews being encouraged to settle in Poland, with almost three quarters of the world’s Jews living in Poland by the middle of the 16th century.

Then reality struck. Understanding the contributions Jews made to Polish society through the ages makes the loss of our people during the Holocaust even more profound. 90% of Polish Jewry perished as a result and we were on a journey to find out more about this devastating period of our history. Standing at the foot of Lublin castle, we heard our first Holocaust statistic of the trip. Of 42,000 Jews in Lublin only 200-300 survived either by hiding or surviving various camps.

After this we were then taken to Yeshivat Chachamei, built in 1930 according to Rabbi Me’ir Shapira’s vision. He successfully encouraged young, religious boys in Lublin into his environment of learning and out of poverty. A few years after opening, Germany invaded Poland and the Nazis stripped the interior of the yeshiva and burned the vast library in the town square. Many of the boys who studied here, managed to escape to the Far East and set up a yeshiva in Shanghai, carrying on Rabbi Shapira’s mastermind, Daf Yomi, that is still adopted today. This left us with feelings of hope, that in the darkest times, goodness lives on.

Next on our itinerary was Majdenak concentration camp, which played a massive role in eradicating many of the Jewish people of Lublin and its surrounding areas. On approach, it was like a nightmare unfolding. The site was enormous and very exposed. As we drove along its periphery, the images I am familiar with from books, films and documentaries were standing prominent in the vast field. Wooden watchtowers, barbed wired fence, wooden huts, a chimney, they all evoked feelings of pure horror.

We made our way on foot to the gas chambers. The first one, primitive and simple intended to murder a dozen or two. In contrast, the other gas chambers on top of the hill, at the rear of the camp were intended to kill thousands with the conveniently positioned crematoria that ensured all signs of each person was wiped off the earth at the hands of evil.

You can read, watch and listen to historic accounts but seeing and touching it magnified the utter despair. It seemed that the next exhibit was harder to take than the previous. It was clear that this vast space had originally been planned to imprison rather than exterminate and prisoners who died as a result of hard labor or due to poor living conditions, well, that was a bonus to the Nazis.

The most shocking part of my experience at Majdenak was seeing the zig zag shaped pits dug out of the grass, where Jewish prisoners were forced to dig a supposed trap for Russian soldiers on 3 November 1943. They were actually digging their own graves where one after the other were forced to lay on top of the previous, after which they were shot. 18,400 Jews, one after the other.

The overbearing stone monument to the left of these trenches rendered everyone speechless. No one had words, just thoughts, but even then, I struggled with these. I felt overbearing anger. What makes anyone more superior to inflict this on a whole people? And now ashes are all that’s left. 100,000 people lay in this hell on earth. I felt sick.

Clive pointed out the view of the town that surrounded the camp. He asked us: ‘What would you do if you saw thousands of people being shot in the concentration camp from your kitchen window?’ If you intervene, you and your family die. Everyone lived in fear. Also, what could one person do? How and who would you confront about this? This opened up a debate within the group, but then we seemed to become tongue-tied in our empathy and desperation in wanting to have been able to save all of these people. Overall, it goes without saying that the putrid smell that bellowed out of the crematorium’s chimney on a daily basis was an obvious sign to the residents of the city of Lublin that people were being exterminated and no one raised an eyebrow. As Clive kept reminding us, he saw it was his duty to encourage questions and debates to help us gain deeper understanding. He had a skill of not only explaining the sights we saw with great historic detail, but also delivered this information with a humanistic element, ensuring we didn’t just learn but encouraged us to question.

Our group felt the need to hold back from our descent of the ashes monument on hearing a group of Israelis singing Hatikvah and felt the need to join in. In sorrow, defiance and hope, this poignant moment helped us all to feel unified and united.

Boarding back onto our coach felt uncomfortable, being able to leave Majdanek, when hundreds of thousands before never had the same luxury. On we travelled towards our hotel for the night in Zamosc, where after dinner we had a chance in our group to hear from each other about what brought us on this trip.

Day 2

An early start saw us heading towards Belzec death camp. This clinical looking monument was hard to digest. Volcanic rocks covered the entirety, surrounded by grey walls and twisted, rusted iron bars. The symbolisms of the memorial had me thinking about the nauseating nightmare that took place here, but I really struggled to comprehend how the murder of 600,000 Jews, Poles and minorities took place here in nine short months and at such a small site, in total contrast to the expanse of land seen at Majdanek.

Space wasn’t exactly needed thanks to the Nazis organised slick conveyer belt of death in this concentrated space of land. Surrounding towns were forcibly emptied, with only one thing the focus, Aktion Reinhard. Jewish bodies still lay amongst the land here, denied of all dignity, having being regularly ploughed after becoming farmland once the camp was raised to the ground and actually having crops grow from the very soil where human remains lay. I couldn’t help turning to the large oak trees that surrounded the small periphery. Only they know the horror that unfolded here.

We spent a short time in the museum, reading profound quotes and hearing the very few testimonies that came out of this camp. We made our way as a group, down the symbolic narrow passage that ran through the middle of the site. It evoked feelings of no escape and claustrophobia leading towards the site where the gas chamber once stood. With no way to trace the hundreds of thousands murdered here, the wall at the end displayed inscriptions of common Polish first names that represent just some of the men, women and children who vanished at the hands of the most barbaric crimes. Clive led Kaddish by the monument wall and we made our way back to the coach along the memorial path that encircles the entire site, which bears the names of all the communities of the Jewish victims that were murdered here.

Onwards towards Lancut, where we soaked up the yiddishkeit of the 16th Century. Standing in the baroque style shul, built around 1726, we gleaned an insight of Jewish life with thanks to Clive, who made use of the overbearing, marbled, four-pillared Bimah, his voice resonating around the huge walls with Jewish prayer. We heard about the vibrant Jewish community in and around the streets where this shul stood. The magnificent wall paintings emblazoned throughout are a reminder of the thriving community that lived here almost 500 years ago and acts as a testament to what it once was.

At lunchtime we sat in the grounds of Lancut Castle, once home to the Lubomirski family who had granted Jews many privileges and later the Potoki family who ensured that the fire in the shul, inflicted by the Nazis was extinguished. Our visit to Lancut was March of the Living’s way of offering us a celebration of life amongst the darkness of the Holocaust.

In contrast we later found ourselves standing in the Buczyna Forest of Zyblitowska Gora. Here we learned the heinous methods that 6,000 Jews and gentiles, men, women and 800 of them children were murdered and buried, whether dead or alive. Standing amongst the mass graves it was so incredibly out of my realm of understanding to comprehend how human beings can perpetrate such atrocious crimes.

Under the stillness of the trees, we learned that of the SS officers chosen to carry out these odious acts, 5% had refused. This even too barbaric for some Nazis. That was just about enough for me to hear. To walk away from this site left me guilty. How can such innocent souls be left all alone in the middle of a forest?

That night we visited the Jewish Community Centre in Krakow that gave us all a bit of a boost. On hearing a passionate speech from Jonathan Ornstein, the Executive Director, I couldn’t help but feel uplifted and positive about the Jewish community in this city. It seemed that despite there being only 100 people living in Krakow according to official statistics, there were actually 700 registered with the JCC. The examples he gave were of a new generation only recently learning that they are Jewish after their grandparents feel an urge to confess the secret they have kept from their family for 70 years, due to fear instilled into them during the Holocaust. They feel intrigued and seek out to connect with the Jewish community. Many of them volunteer or work at the Jewish Community Centre, alongside 60 non-Jewish young people who want to learn more about being Jewish.

It seemed that with every ray of hope, we were brought back to the reality of why we were in Poland. We were fortunate to listen to Arie Shilansky‘s story of survival in the Siauliai Ghetto in Lithuania and later, Dachau labour camp. We heard how his family are living proof of the victory of good over evil and the strength of the Jewish people.

Day 3

After spending time visiting three notable shuls in the Jewish quarter of Krakow, it was now time to make the journey to Auschwitz for the rest of the day, spending the rest of the morning at Auschwitz I.

This felt very clinical. Each infamous barrack had been turned into a museum with exhibits that portrayed its history. It felt like a film set, methodically laid out and well structured. Thousands of combs, hairbrushes, pots and pans, tallisim, shoes, eye glasses, suitcases, piled so high and running so deep. The beautiful long plaits, curls and locks stolen so callously, denying women and girls of their femininity. Whilst being ushered past these endless glass cases by our Auschwitz guide I felt as though I was on an endless path leads to hell. I struggled to fathom the workings of the punishment barracks, so extreme in every way. Leaving each barrack to move on to the next, it felt as though I was coming up for air.

Being a Jewish organisation, food played an important role on our trip and we received a packed lunch every day on route. Wherever we happened to be on our tour, at lunchtime we would stop to eat, even if that meant Aushwitz. It felt strange and uncomfortable. Here we were, sat on the grass outside the entrance to Aushwitz I. We could have been in any park but when I turned around reality hit me in the face.

We spent the rest of the day 3km away in Birkenau. We were met with the infamous image of the railway tracks leading through the arched brick entrance. The scale of this camp had me gasp in disbelief. It spanned a distance I could not even see beyond, surrounded with barbed wire, wooden watch towers and barracks, some intact, others lay in ruins.

We made our way down the relentless path towards the gas chambers and crematoriums that lay in a heavy heap, crumbled from the Nazis haste to conceal the evil inflicted here. We stopped at the cattle carriage, stationary on the tracks. The facilitator in transporting millions of Jews to their death. It was here that our group’s survivor, Ivor, started to share his personal experience, arriving in Birkenau as a 12-year-old boy. We gathered round him and listened intently about the innocence as a child excitedly watching the train tracks rush by through a small hole in the floor of the cattle carriage.

His memory of feeling unwell as he arrived at the camp, but the luck of being able to understand Yiddish, saved his life after understanding the instructions a fellow Jew had given to the carriage warning the children to pretend to be 16 years old. When questioned by a Nazi, 12-year-old Ivor said he was 16 years old, saving him from the line of death.

We heard how luck played a big part for Ivor during his time in Birkenau and how his brother saved him from death on a number of occasions. We could also see the pain he felt in talking about these experiences, magnified even more by standing in the very place he last saw his parents and seven of his siblings who were murdered on arrival.

He struggled with the experience of being back in Birkenau but knew the importance his presence had in the group, especially to his daughter and granddaughter who were accompanying him. It was a privileged experience to hear from a survivor amongst the camp ruins, one that the next generation soon won’t have.

Clive led Kaddish whilst standing inside one of the infamous wooden huts, where only 73 years ago witnessing nine bodies to each rickety wooden bunk bed. This really was not that long ago. Monstrous crimes were committed against humanity in modern times, perpetrated by a nation of culture and intelligence. How and why? There seemed to be no answers where we were standing, just sheer devastation.

That evening we all came together for the Yom Ha’Shoah ceremony, held at the Galicia Museum in Krakow. We heard from the inspiration behind March of the Living UK, Scott Saunders. Sir Eric Pickles (UK Special Envoy for post-Holocaust issues, former government Minister, former Chairman of the Conservative Friends of Israel) and Joan Ryan MP (Chairman of the Labour Friends of Israel), spoke with real passion and emotion, showing that they really are committed to their support and friendship of the Jewish community.

Day 4

We heard many stories of heroism and bravery whilst standing in the square. Only a small piece of the Ghetto wall stands today, intentionally shaped to look like tombstones during the barbaric imprisoning of the Jews. Chairs artistically stand as a monument, representing an absence of people from this area that saw so much death.

Our return to Bikenau the following day marked the end of our educational tour. We started the march alongside 11,000 people from around the world who had travelled with March of the Living International. From Belguim to Mexico and India to Argentina, young and old stood side by side on the site of Aushwitz I to start our 3km trek towards Birkenau. It wasn’t until the sound of the shofar blasted through the speakers around the camp, signaling the march had begun and then the Israeli contingent began singing with real Israeli gusto.

Once out of Aushwitz I, the main roads were lined with local Polish residents waving and shouting ‘Shalom’ along the way. I was even handed a leaflet from a Korean, apologising for the Holocaust. I built up some speed with my fellow marchers and we were soon at Auschwitz Birkenau, with a sea of people in front and behind us. This experience was filled with joy in seeing smiling faces and calls of support from passersby, a far cry from the experience prisoners had when making the same walk to their death under armed guard.

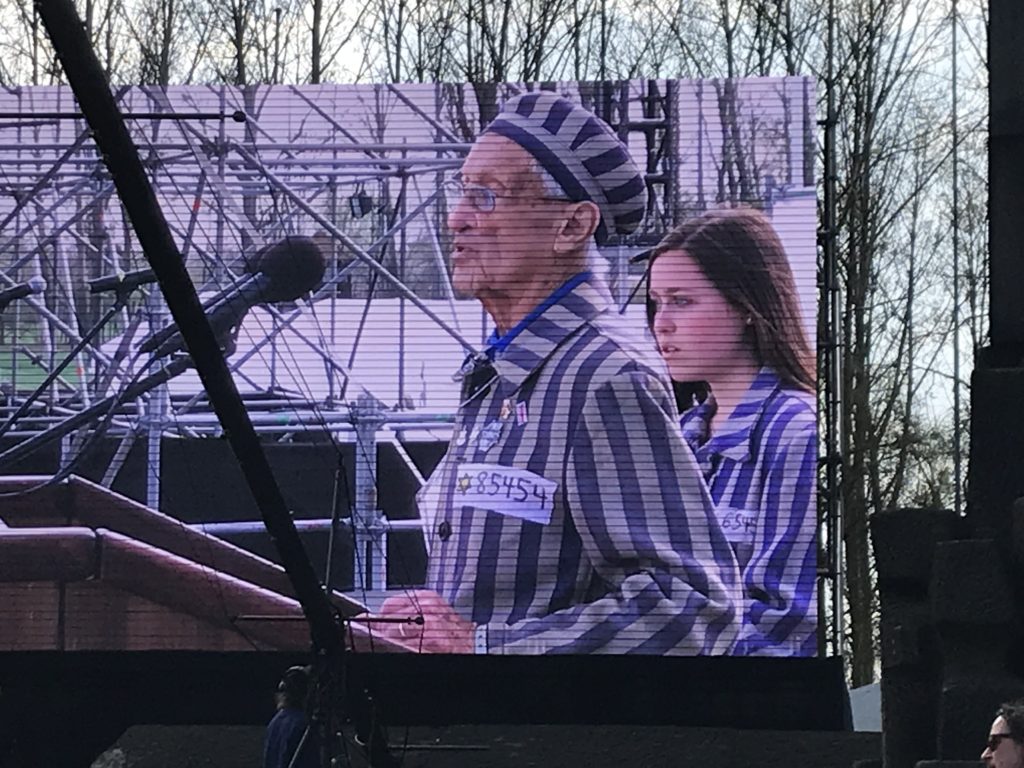

On arrival at Birkenau we all gathered at the far end of the camp to watch the March of the Living ceremony in the hot, blazing sunshine. We heard from President of the State of Israel, Reuven Rivlin and Polish President, Andrzej Duda and Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, the former chief Rabbi of the State of Israel, a child survivor aged 8. All gave powerful speeches of remembrance. Edwards Mosberg, Mauthausen camp survivor, stood on the stage alongside his granddaughter, both wearing concentration camp striped uniforms. He shouted and cried throughout his speech until he could barely stand up straight. We heard how his whole family perished and the nightmares he still has 73 years on. This was real anger and hatred which I have rarely seen before. He was re-living every word he spoke. Time flew by whilst listening to such influential speeches but we were beckoned by our bus leader, Michael and we headed towards our coach for the final time. Our March of the Living experience had come to an end and as we headed towards the airport we reflected on the day.

The weather had been a juxtaposition throughout our 4 days in Poland. I had been used to seeing photos, documentaries and films depicting the sights of the Holocaust in black and white and expected a dark grey mist to hang above us on our journey. I found the whole experience disturbing for so many reasons and what I was struggling with was how can the sun be shining? Surely the sun denotes happy thoughts and here we were standing in a nightmare. I struggled with the images I saw at Birkenau on the day of the march where there was easy access to fresh bottles of water at every turn and empty bottles strewn across the bin areas. The insatiable thirst that prisoners endured would have been beyond all comprehension and here we are today privileged, lucky and free.

Poland impressed me with its hidden treasures of the past and legacy imbedded in the respectful monuments and museums that stand tall, showing the pain, suffering and loss of the Jewish people at the hands of Nazi occupied Poland. President Rivlin summed up my trip to Poland in his speech at Birkenau, ‘This land was a forge of the Jewish Soul and to our deep sorrow, also its largest Jewish graveyard.’

March of the Living UK is impressively organised. My group, along with the seven others were given the opportunity to see, hear, touch and smell the hideous crimes Nazis inflicted on 6,000,000 along with 3,000,000 Poles and many others from a different ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and political beliefs. Whilst some Poles helped rescue Jews during the Holocaust, with only a small percentage of those known being given the honour Righteous Among Nations, others took part in their extermination. For anyone who insists on denying the Holocaust should take the same trip. It will leave a hole that cannot be filled. It will live with me for a long time to come.